To borrow a cliché from sports commentary, this year’s local elections can be interpreted as a ‘game of two halves’.

As we saw last month (first 658), those elections delayed from 2020 because of the pandemic mostly reprise contests previously held in 2016 when Labour and the Conservatives emerged neck-and-neck.

Against that background, Labour Leader Sir Keir Starmer MP has some justification in calling them ‘tough’ for his party, which is currently some way behind in the polls.

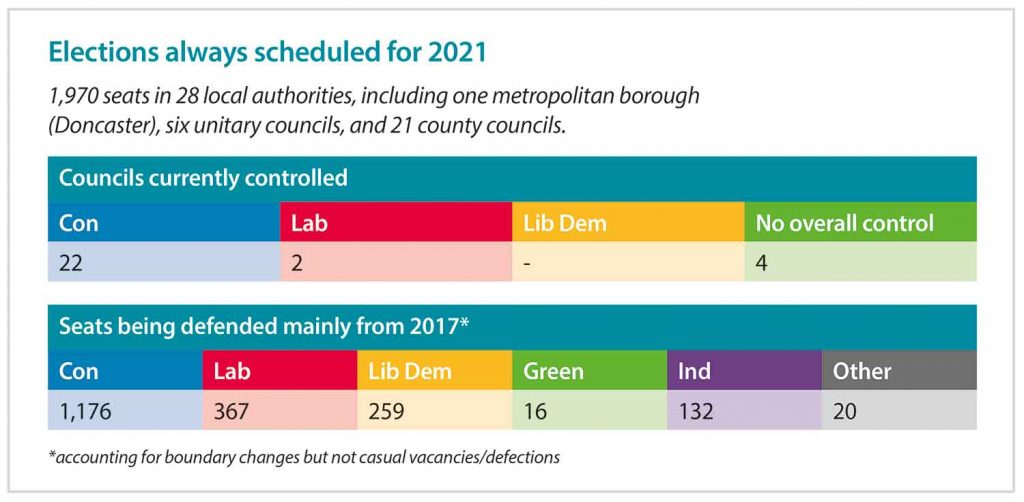

The elections always scheduled for this May come with an entirely different context.

Four years ago, the Conservatives were well ahead of all comers, beating Labour by more than 10 points in our calculation of the national equivalent vote.

And it is no doubt with that in mind that Amanda Milling, Conservative Party Co-Chairman, has engaged in her own expectation management by claiming that her party will be defending ‘an incredibly high base’.

In 2017, the Conservatives gained almost 400 seats and took control of an additional nine councils, with both Labour and the Liberal Democrats falling back. Among the 27 English counties, they won more than two-thirds of all the seats and an overall majority in all bar three of them.

This year, however, only 21 of those county councils have repeat elections. Dorset and Northamptonshire have been sub-divided into unitary authorities, and Buckinghamshire becomes a whole county unitary.

Three other counties – Cumbria, North Yorkshire, and Somerset – have had their elections delayed, pending local consultation on possible structural change.

In a dozen or so counties, the Conservatives are so far ahead of the main opposition that even modest losses are unlikely to impact on their ability to control the local administration. A handful of counties are more competitive, though.

Derbyshire has a history of swinging dramatically between Labour and the Conservatives. In 2013, Labour gained 20 seats there to win control and then lost almost all of them in 2017 as the Conservatives turned the tables.

Labour’s fortunes dipped still further at the 2019 General Election, losing three more of its MPs – including Dennis Skinner in his former Bolsover stronghold – such that it now holds just two of the county’s 11 parliamentary constituencies.

A swing of just three percentage points from the Conservatives since 2017 is needed to put Labour back in charge at County Hall. This is Labour’s best chance and surely a ‘must’ if the party is to claim a successful night.

The exchange of seats in Lancashire in 2017 was more modest, but sufficient nonetheless for the Conservatives to dethrone Labour as the largest party and take overall control themselves.

Their four-seat cushion is vulnerable to a less than two-point swing to Labour, with three of their most marginal seats to be found in Rossendale – where there is a tightly fought district council election too.

The Conservatives have had a majority in Nottinghamshire only twice since 1974 and fell just short last time. Labour, damaged also by the success of local Independents in 2017, must at least aim to replace them as the party with most councillors.

A five-seat turnover would do the trick, but obvious marginal chances are thin on the ground.

The postponing of elections in Somerset will have disappointed the Liberal Democrats, who won three of the county’s four districts in May 2019 and had seen a prospect of making more inroads into Conservative territory.

Their attention may now turn to Cambridgeshire, another county where they have had some district-level success. They polled more votes than the Conservatives in South Cambridgeshire in 2017, won the district council by a country mile in 2018, and at least three divisions (and four seats) there could now fall to them.

Labour did win one of the ‘county’ unitary councils with elections in 2017 – Durham. But the party’s majority has become precarious thanks in part to defections by sitting councillors.

Having lost three formerly safe parliamentary seats (including Tony Blair’s old Sedgefield constituency) at the 2019 General Election, the party cannot afford more reverses.

It is salutary to recall that as recently as 2013, three-quarters of all councillors here were Labour.

Northumberland is a more naturally politically mixed council area, with rural and prosperous suburban parts together with close-knit urban communities in places such as Ashington and Blyth.

The Conservatives fell just short in 2017, aided by a further collapse of the Liberal Democrats who had been the largest party as recently as 2012. As in Durham, though, the main focus will be on the nature and extent of any Labour recovery.

“The elections always scheduled for this May come with an entirely different context”

Elsewhere, Shropshire and Wiltshire look certain to stay Conservative as probably does the Isle of Wight.

The number of seats in Cornwall has been drastically reduced to 87 from 123, following a boundary review. Only the Liberals Democrats have ever had overall control there, but with the party still in the doldrums and Independents remaining strong, another ‘hung’ council looks a sure bet.

May 2017 also marked the inaugural elections for six combined authority or ‘metro’ mayors. In three cases – the West Midlands, the West of England and Tees Valley – the Conservatives prevailed by a narrow margin that they must now defend.

In the West of England, where turnout in Bristol is likely to be higher than in Bath or South Gloucestershire because of coincident city mayor and council elections, Labour could benefit from the redistribution of Liberal Democrat and Green second-preference votes more decisively than it did last time.

The Conservative mayors in Tees Valley and West Midlands – Ben Houchen and Andy Street – have built relatively strong local name recognition, which will assist them in what has traditionally been Labour territory.

Mayor Houchen will be hoping also to benefit from recent Treasury largesse for the area, which has seen both freeport status and the proposed establishment of a civil service ‘economic hub’ in Darlington.

But although the Conservatives now hold four of the Tees Valley’s seven parliamentary seats, this really should be a Labour ‘red wall’ heartland. The election also has a curiously old-fashioned flavour, featuring just Conservative and Labour party candidates.

The challenge for analysts is in drawing a balanced conclusion about the parties’ performance from such a varying set of elections. The disparity in benchmarks can clearly be seen from a handful of local authorities that had directly comparable local elections in 2016 and 2017.

In Harlow, for example, Labour’s share of the vote was 40 per cent at both the 2016 district and 2017 county contests. On the other hand, the Conservative share leapt from 35 per cent to 51 per cent, largely as a result of sweeping up former UKIP support.

In Lincoln and Tamworth, the Labour vote was similarly static, with the Conservatives jumping by more than 10 and eight percentage points, respectively.

The current national opinion poll lead for the Conservatives suggests that Labour could lose seats it won in 2016; conversely, the party must demonstrate progress since 2017, when it posted its worst local electoral performance in opposition since the time of the Falklands war almost 40 years ago.

There is the real possibility that a mixture of gains and losses on both sides could impact on the pattern of council control while appearing to deliver little net change in seats overall. Such an outcome is likely to keep the spin doctors busy as the results of the covid-impacted count trickle out in the days after 6 May.