The unprecedented decision to stage two cycles of English local elections at the same time means that we need to focus on the contrasting past outcomes in two separate years to make any sense of what might happen this May.

Those of this year’s local elections postponed from 2020 because of the pandemic take us back to a now unfamiliar political landscape.

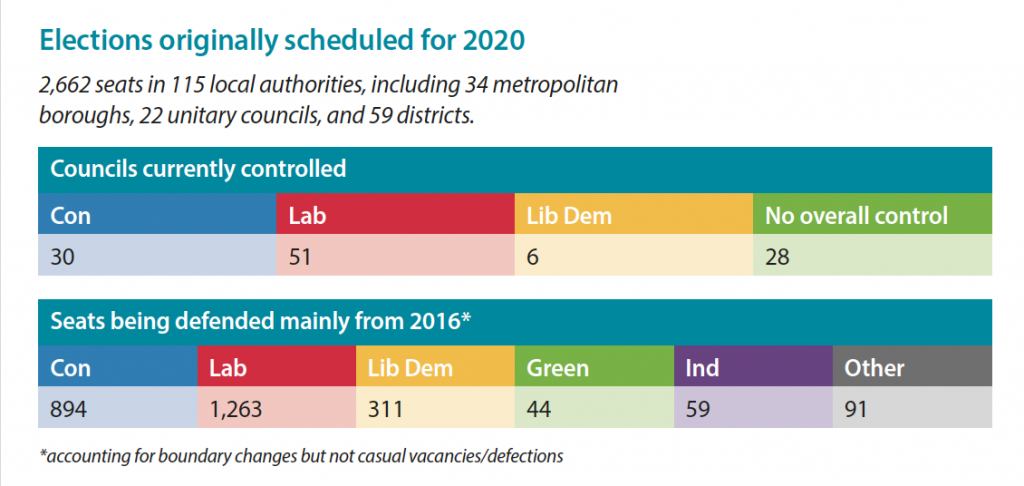

Most of the seats being contested across 115 councils (see table, below) last fell vacant in 2016 – just seven weeks before British politics was turned on its head by the result of the EU Referendum.

David Cameron led a majority Conservative government – his 2015 general election victory marking the party’s first such triumph in more than two decades. Jeremy Corbyn was little more than six months into his term as Labour leader and facing his first real electoral test.

And the Liberal Democrats, continuing to suffer following their involvement in the 2010-15 coalition government, appeared to be languishing well behind UKIP.

In truth, the May 2016 local elections were a rather humdrum affair giving little indication of the turmoil to come.

Both Labour and the Conservatives registered a small decline in seats and councils controlled, and no party gained or lost more than 50 seats net.

Our estimate of the national equivalent vote put Labour one point ahead of the Conservatives with the Liberal Democrats just beating UKIP into third place for the first time since 2012.

So what does that benchmark foreshadow for what might happen this time? With no by-elections to guide us but with the Conservatives out in front in the polls – thanks in good part to the perceived success of the vaccine rollout – Labour does look to have its work cut out just to stand still. Indeed, Leader Keir Starmer MP is already in the business of managing expectations by declaring that the contests will be ‘tough’ for his party and that a swing to the Conservatives might be expected.

The metropolitan boroughs have long been considered Labour’s heartland. The party took more than 45 per cent of the vote and won three-quarters of the seats there in 2016. There was a similarly dominant performance in 2018, but in 2019 Labour went backwards overall despite gaining control of both Calderdale and Trafford.

In some areas that became tagged as part of the ‘red wall’, the party’s support slumped. In Barnsley, South Tyneside, St Helens, and Sunderland, there was a double figure decline in vote share compared with 2016.

With only a third of seats up for election, Labour is certain to retain control of these councils, but the party needs to demonstrate it has recovered at least to 2016 levels.

More competitive councils like Bury, Dudley and Trafford merit close attention. Labour is just short of a majority in Dudley and on paper needs only a small swing to gain Belle Vale and Gornal wards. However, the Conservatives won both easily in May 2019, ahead of gaining Dudley North at the general election.

“If Labour needs to fight hard to hold its ground from 2016, the Liberal Democrats are faced with continuing the task of building back their local government base from the bottom up”

Large majorities in individual wards in Bury should help Labour hang on (though the Conservatives narrowly gained both constituencies there in December 2019). Trafford, a Remain voting area in the south Manchester conurbation, has been trending Labour in recent local elections and ought to be safe.

Among the unitary councils held over from 2020, there are all-out elections in Bristol, Halton, Hartlepool and Warrington. Labour has struggled to maintain a formal majority in Bristol, but is far ahead of the opposition parties and should retain the city mayoralty too.

Local politics in Hartlepool has been chaotic in recent years, and the town has now been thrust into the national spotlight with a parliamentary by-election likely to be held on the same day as the locals.

The outcome of both contests is unpredictable and may come down to the choices presented to electors.

The Conservatives will be seeking gains in Peterborough to make their hold on the council more secure, but are handicapped by having to defend the bulk of seats falling vacant this time and thus having limited opportunities to make progress.

In Plymouth, Labour’s apparently narrow majority has already been boosted by an acrimonious split in the Conservative opposition group.

District councils that hold elections by thirds tend to be concentrated in more urban areas, so here, too, Labour must be wary of any perception that it has slipped back since 2016. Councils like Ipswich and Lincoln remain solidly under the party’s control despite parliamentary losses to the Conservatives 16 months ago.

Crawley has had a Conservative MP since 2010, but the local authority has swung between the two main parties over that period. It now could not be closer.

They polled the same share of the vote at whole council elections following boundary changes in 2019 and each defends six seats from then. With employment at Gatwick airport badly hit by the collapse in air traffic, post-election bragging rights could take on wider significance.

There are similarly close Labour-Conservative battles further north. A strong Labour performance in Rossendale in 2016 saw the party win 10 of the 12 seats contested. A single seat loss now would deprive it of an overall majority.

Labour appears to have more of a cushion in Amber Valley, but holding off the Conservatives in a council they held for two decades until 2019 would be a symbolic success nonetheless.

Welsh by-elections

Although a dozen or so local by-elections have taken place in Scotland either side of the strict winter lockdown, there had been no such contests in England or Wales for a year.

Wales, however, has now begun to dip its toe in the water and 18 March saw electors in three wards go to the polls.

There was an Independent hold in Conwy, and Plaid Cymru kept the seat it was defending in Denbighshire. In the Maesydre ward in Wrexham, though, Plaid registered a gain from Labour.

The slump in Labour’s vote compared with 2017 is not a good augury for the party.

If Labour needs to fight hard to hold its ground from 2016, the Liberal Democrats are faced with continuing the task of building back their local government base from the bottom up. Councils like Cheltenham, Eastleigh (Liberal Democrat since 1994) and Watford remained loyal even through the dark days of the coalition, and they have gained Mole Valley, Three Rivers and Winchester during the past three years.

Their rare general election victory in St Albans will give them hope of getting closer to control (they won 11 wards there in 2019 compared with six in 2016), and it may be that the coincident county council elections elsewhere in southern England will also prove fertile territory.

In three authorities, though, the elections postponed from last year have 2017 as their point of comparison.

The newly created unitary authorities in Buckinghamshire, North Northamptonshire, and West Northamptonshire have inaugural contests based on three seats in each pre-existing county division.

With 147 members, Buckinghamshire Council will be the largest in the country until its boundaries and councillor/elector ratios are reviewed.

Four years ago, the Conservatives won handsomely in each of these three cases – just as they did across much of shire England. They made more than 400 net seat gains and nudged 40 per cent in our calculation of the national equivalent share of the vote. Labour’s share by contrast was below 30 per cent.

The results did not prove a good predictor of Theresa May’s prospects in the 2017 general election held just five weeks later, but they are the base against which the contests always scheduled for this point in the local electoral cycle must be measured.

And that means that it is the Conservatives who could be on the back foot – as we will explain next month.