We will never know, of course, but the Conservatives could have been celebrating their best local election results for nearly three decades.

Not since the contests that closely followed John Major’s surprise General Election victory in 1992 has the party hit 45 per cent in our annual calculation of the ‘national equivalent vote’ – a measure of how the various parties would have fared if the local elections had taken place in every part of the country.

Opinion polls and local by-elections before the lockdown suggested Boris Johnson’s electoral honeymoon would lead to a strong Conservative advance locally, with new targets in so-called ‘red wall’ areas such as Rotherham, Wakefield and West Bromwich (Sandwell), which returned Conservative MPs for the first time ever – or in generations – in last December’s General Election.

Leaked analysis from Labour showed the party preparing for the loss of hundreds of seats and control of councils such as Crawley, Harlow and Plymouth. And it is unlikely that Sir Keir Starmer’s accession to the Labour leadership on 4 April would have come in time to make a radical difference.

Meanwhile, the Liberal Democrats have been leaderless and, in effect, rudderless since yet another disappointing General Election result, and the Brexit Party has disappeared as rapidly as UKIP before it. Currently, there are just 26 councillors across the country who call themselves ‘UKIP’ compared with a high of almost 500 in 2015. The Brexit Party can muster a mere ten.

In such circumstances, the Conservatives seemed to be facing an open goal. But local election triumphs are not always a marker of future success.

Labour’s 44 per cent under Neil Kinnock in 1990 counted for little when the Conservatives were decisively re-elected two years later. Major’s own general and local election achievements were wiped out in a matter of months as Black Wednesday in September 1992 wreaked damage from which he and his party never recovered.

“Johnson risks being derailed by a wholly unexpected event”

The local contests held in the middle of the 2017 General Election campaign were thought to presage a landslide for Theresa May. Instead, the Labour vote surged in the final weeks before polling and she was left a much-weakened occupant of Number 10 Downing Street.

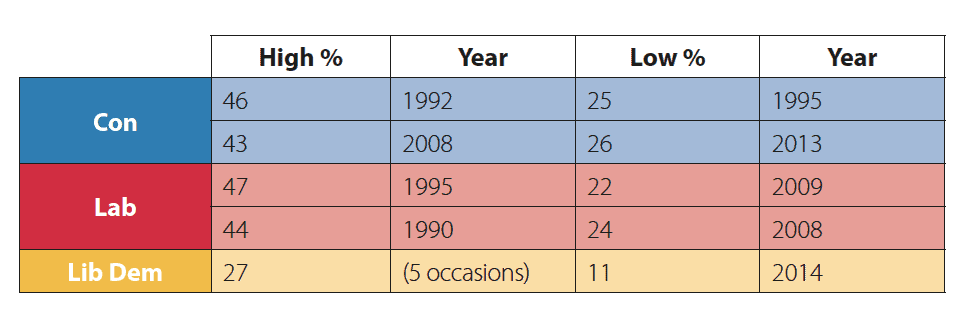

As so often in the late 20th century, it was left to Tony Blair to re-write the elections history books. Labour’s 47 per cent at the 1995 local elections marked the best performance by any party in terms of ‘national equivalent’ share of the vote.

The Conservatives, conversely, slumped to their lowest recorded score of just 25 per cent. And for Blair, of course, this was a sign of things to come, with his party winning more than 400 Commons’ seats in both 1997 and 2001.

His successor, Gordon Brown, was not so fortunate. Badly wounded by the global financial crisis, he presided over Labour’s worst local performances of 24 per cent in 2008 and 22 per cent in 2009.

Like Major and Brown before him, Johnson now risks having his premiership derailed by a wholly unexpected event. By the time almost every elector in Britain has the opportunity to vote in an election of any kind in May 2021, the electoral landscape could look very different to that of this year’s hypothetical contests.