A long-standing issue for local government has been the recruitment of women councillors, with the LGA’s 2018 councillor census showing 36 per cent were female.

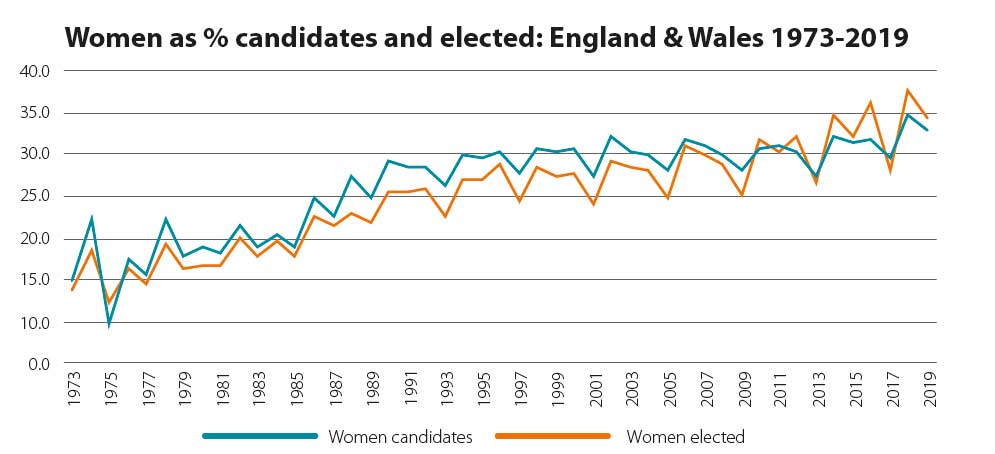

Back in 1973, in the first elections to what were newly formed councils, women comprised just one in seven candidates. Since women formed a similar percentage of those elected, the conclusion was that voters did not discriminate for or against women on the ballot paper. However, with so few women competing for office a recruitment drive was required.

This was not just a local government problem. The proportion of women standing at the two General Elections in 1974 was less than half the local government figure, while the proportion elected was less than a third.

Women were also notable for their absence in the professions and in management roles.

But it was another decade before women councillors rose to one in five of councillors elected. To an extent, change was slow because of male incumbents who understandably wished to continue in post.

Another problem lay with the recruitment of more women candidates. Local parties either seemed unwilling or unable to alter the gender balance.

The mid-1980s, however, brought a step-change. How much this was related to having a female Prime Minister or the much wider debate about women’s empowerment is difficult to say, but the evidence is clear: by the end of that decade, women had risen to three in 10 candidates although a lower fraction than that were being elected.

The continuing gap between the percentage of women standing and being elected reflected some continuing recruitment issues. Evidence from candidate surveys shows women were more likely than men to stand after being asked by a fellow party member.

Women were also more likely to say that they were standing to assist their party’s ambition of contesting seats – a case of standing without the fear of being elected, perhaps.

“Progress in improving women’s representation has been made but some will claim it has been slow and should be accelerated”

The pattern of local parties performing better than the parliamentary equivalent continued until the mid-1990s, when the Labour party’s decision to establish women-only shortlists and take other measures promoting positive discrimination had an impact.

There were 101 women among Labour’s tally of 418 MPs following the 1997 landslide victory.

While the overall rise of women candidates had stalled locally, the proportion elected began to improve. A gap between selected/elected of about three percentage points fell to just one point. The 2006 and 2007 local elections saw the percentage of women elected pass the 30 per cent mark for the first time.

Women’s recruitment examined through the lens of party politics shows some interesting developments. During the 1980s and 1990s, Labour locally could not quite match either the Liberal Democrats or the Conservatives. Women elected in 1991, for example, comprised a third of Liberal Democrat councillors, a quarter of Conservatives and just over a fifth among Labour’s intake.

Yet, by the time of the equivalent point of the local electoral cycle in 2011, the picture had changed. Now, women were 37 per cent of Labour’s elected intake, a figure that was 10 percentage points better than the Conservative’s.

Labour’s rapid recruitment and placement of women into winnable seats explains the narrowing and eventually the reversal of the percentage gap between women selected and elected.

Some 32 per cent of candidates that contested the 2016 elections were women but among those elected the figure was 36 per cent. Among Labour councillors elected then, the proportion of women reached 43 per cent, increasing its lead over rival parties.

Elections results from 2019 show the latest picture. The figures for women standing as Conservative, Liberal Democrat and Labour were 30, 33 and 39 per cent respectively.

A quarter of all Independents were women and among the smaller parties more than a third of those on the ballot were women. In Wales, Plaid Cymru’s women candidates formed a quarter of its total in 2017.

However, some 44 per cent of Labour’s intake in 2019 are women, further demonstrating the party’s desire to redress the imbalance among the sexes. The Liberal Democrats and Conservatives too saw a fractionally larger proportion of women elected compared with those standing.

Progress in improving women’s representation has been made but some will claim it has been slow and should be accelerated. This may be easier said than done.

Close examination of the trend reveals another feature of women’s recruitment that is related to the electoral cycle. A four-yearly dip in the data corresponds with the English shire county elections, revealing that women are more difficult to recruit to these councils.

If this feature relates to the geographical spread of these authorities, then it may have implications for the practice of amalgamating small districts into large unitary councils.