The pandemic has concentrated attention across the world on the philosophy and practice of remote voting.

In a handful of countries including Canada, Estonia, and Switzerland, elections of one kind or another have been conducted using online voting over the internet. In most places however, including in England and Wales, it is voting by post that has expanded to save electors having physically to go to the polls.

Like so much these days, though, it is an issue which can spark fundamental political divisions.

For those on the left, anything to make the process of voting easier and more inclusive and to help bring ‘disadvantaged’ groups into the electoral arena is a good thing. Right-wingers, conversely, worry more about potentially less secure methods of casting a ballot and a greater incidence of fraud.

The argument is currently being played out in the early skirmishes of the US presidential election. Donald Trump is raging about the likely increase in ‘mail-in ballots’ this November and trying to sow doubts about the integrity of an election in which they form a substantial fraction of the votes.

The Democrats, on the other hand, are keen to expand the eligibility to vote by post, including cases in Alabama and Texas currently before the courts.

In Britain, all electors were given the right to ‘demand’ a postal vote under the terms of legislation introduced by the first Blair administration in 2000. Since then, and not least following a damning ruling by an Election Court under Richard Mawrey QC about events in Birmingham in 2004, significant amendments have been introduced to improve the security of the system.

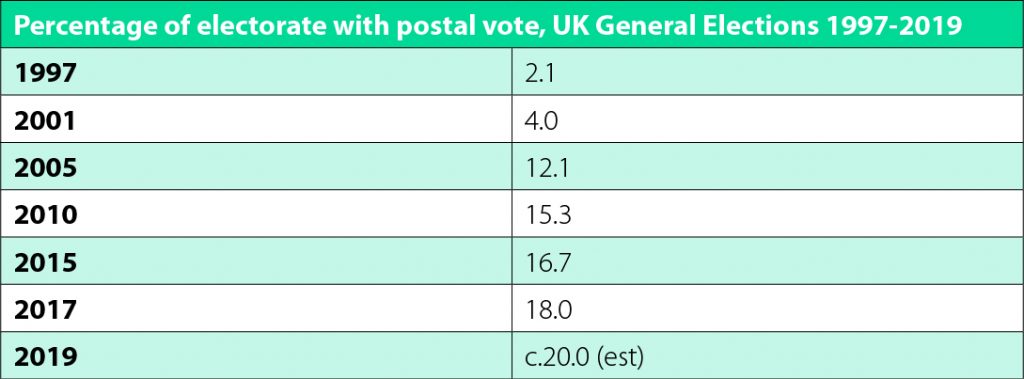

Nonetheless, in the past two decades the proportion of the electorate able to vote by post has risen from just 2 per cent to almost a fifth (see table, below). The impact of coronavirus is likely to increase this number still further when (and if) elections resume next May.

It is clear, however, that the attitude and zeal of local administrations and political parties continues to lead to substantial council-to-council variations in take-up.

In Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Stevenage and Sunderland, for example, postal voters number between a third and 40 per cent of all electors.

Apart from each being under Labour control, all these authorities had experience of conducting all-postal ballots as part of pilot schemes conducted in the early 2000s.

Although the hangover from that cannot be discounted, other councils with a similar pedigree have much lower levels of electors opting to vote by post. In Halton, the figure is less than 9 per cent, in Hull it is just over 10 per cent, and in Liverpool it is 13 per cent.

There can be little doubt, though, that turnout is higher among those with a postal vote, whether because they are already more engaged or simply reflecting the ease of the process. In Newcastle-upon-Tyne at the 2018 local elections, for example, it was 67 per cent for postal voters but less than 23 per cent for those who still needed to visit a polling station. In Liverpool the two proportions were substantially similar.

Some argue that the greater prevalence of postal voting has only served to disguise a continuing crisis of participation among some groups. What remains less certain is which if any political party systematically benefits from a wide roll-out of postal ballots. Their impact will vary from place to place, but no one party can be confident that it will always be the ‘winner’!